Recently I’ve been working with a group of young writers, offering feedback on their works-in-progress. It’s got me thinking about critiquing and about receiving criticism. In my writing life I’ve experienced two broad categories of criticism, and lots of variations between: the first kind delivers renewed faith in my ability and energises me to tackle my writing problems; the second leaves me paralysed with despair, questioning whether I ought not just give it all away.

Can you relate to either of these experiences?

In this post I’m looking at tips to consider when giving and receiving criticism. A caveat: I am not a professional editor. I am a novelist and a teacher of creative writing with time spent on each end of the reviewing seesaw. If you’re up for it, join me on this crucial part of the writing journey. I would love your input.

Why have your work reviewed?

I have yet to find anything in the revision process that equals the value of frank, supportive feedback from a trusted reader. Novelist Robert Stone likens the revision process to trying to cut your own hair. You may sense that your story needs improving, but without a clear picture it’s hard to get it right. Stone says that an external reader may not be able to tell you how to style the material, but they can hold up a mirror to help you see beyond your normal range of vision.

Writer’s tip: during the manuscript process, carefully consider who you hope to review your work. Your family and friends may love every word you write, but unless they can pinpoint and articulate your story’s strengths and weaknesses, they are probably not the best means of advancing your story. An independent reviewer, a writing colleague, an astute reader, a teacher or mentor, one whose opinion you respect (perhaps even tremble at a little), may be better equipped to offer practical, productive guidance. This doesn’t mean you are compelled to agree with or act upon every point of call. You are the referee of your own story, free to consider each problem and solution.

First flush

The term first flush refers to the first plucking of a tea plant during harvest season, said to yield the purest tea the plant is capable of producing. A reviewer’s ‘first flush’ reading of your work, free of the echo of earlier drafts, is likely to offer the premium yield. That crucial ‘first read’ invites keen observations and astute queries. Unless you have an unlimited bank of trusted readers vying to see your work-in-progress, be strategic about who you will ask to read your work, and at which stage of the drafting process. If you have the luxury of more than one reviewer, look to each of them as yielding a ‘first flush’ reading. Invest wisely.

Writer’s tip: requesting someone to review your writing, especially a novel-length work, is a big ask, best approached with consideration. Such a review amounts to an extraordinary act of generosity and a monumental undertaking on the reviewer’s part. If the reviewer declines your request, be gracious. If they agree, be sure to acknowledge them for their time and input. Needless to say it would be poor form to expect someone to review your work if you were unwilling to contribute in kind.

Respect your reviewer

The degree of effort and attention a writer puts into their draft is sure to have a boomerang effect. When I read a work that demonstrates care and polish, I know I have been entrusted with something deeply important to the writer. But when a work is riddled with typos and poor grammar, where parenthetical notes indicate incomplete business, the review process feels disruptive, at worst dispiriting. You need your reviewer to be on your side, to see your commitment and to want you to succeed. Author Joyce Carol Oates likens the readers’ role to that of ideal editors: a friend of the text and a friend of the writer. Compare the interaction to any important endeavour: it wouldn’t be in your best interest to rock up to an interview without considering your appearance or preparing as best you can. Recently a writer emailed me their work for review. In the week that followed I received multiple updates with instructions to ignore the previous versions. A reviewer is donating their time and expertise. Enough said.

Encouragement, false praise and brutal blows

Do you remember your earliest days of creativity, when the act of forming letters on a lined page, or making up stories, or drawing or painting or colouring-in was unadulterated fun? Do you remember your earliest artistic creations and the joy you felt at a teacher or parent’s words of praise?

What went wrong?

Well, nothing went wrong, other than adulthood. The downside of developing and honing a skill is a rise in self-awareness and with it the inevitable onset of an inner critic. I respond positively to encouragement. We all do. I suspect so much of the child resides in us all. As I write, and when I review my writing, my inner critic is all too ready to give me a serve of self-doubt. I have to listen to that harsh little voice, I can’t ignore it, but left unchecked, our inner critic holds the power to unravel the positives: creativity, confidence, drive, motivation.

An external voice, one that is measured and perceptive, will look to both the strengths and shortfalls in your work. It will offer praise, encouragement, guidance. That said, is there a place for false praise? And how does the need for encouragement position words of actual criticism?

False praise is about as counterproductive as brutality. As a reviewer you are ultimately doing the writer a disservice not to be up front about areas of the writing that need work. At the same time, a sole focus on the negative does not offer a measured review. I haven’t yet read a piece of writing in which there wasn’t something to admire. Acknowledge those high points. I am mindful when asked to review a work of how far along the writer is in their journey. For some, this will be their first experience beyond school at receiving a review unquantified by a grade. As reviewers, the language we use is paramount. Match the tone and advice to the individual. Be clear. Be kind. Put yourself in the writer’s head and imagine receiving your review.

As for brutality, I can’t think of a single positive thing to say about it. The objective of a review is never to crush the writer’s confidence, but to enable the writer to see both the strengths of their work and where it may fall short—to offer strategies that advance the work to become the best that it can be. Writing is a courageous undertaking, a commitment of hours and effort, a never-ending school of learning. I’ve always loved this philosophy from my creative writing professor Dan Mueller at the University of New Mexico, back when I was a writing student. Dan’s words introduce a creative writing workshop, but can as easily apply to any writing or review situation:

I believe that every piece of fiction has contained within it the blueprint, or seed, of what it ultimately wants to be. For the author, fully realising a piece of fiction requires carefully listening to what the narrative is telling you during the act of composition, from the first sentence to the last, and at every stage of revision. In this way, pieces of fiction are born. —Dan Mueller

How will a review best serve writer and reviewer?

Picture this: the writer has completed her third, sixth, thirteenth, nineteenth draft. Whichever number it is, she tells you she feels close to completion and asks for your feedback. Before undertaking a late-stage reading, it behoves reviewer and writer to clarify their intentions. Is the writer being clear (and honest) about what they want from a review? If it came to the crunch, would the writer be willing to discard and rewrite, or have they travelled way beyond that point? You may be asked to review a manuscript limited to word and line-level comments. Does the writer fully appreciate the time and expertise involved in any form of review? I was asked once to review a multi-page grant application. ‘It just needs a light edit,’ I was told. More of a light kidney transplant. Perhaps you’re being called upon because your particular expertise in life fits the subject matter of the work, independent of writing craft. Are you willing to tailor your reading to the request? If not, think carefully about taking it on.

Writer’s tip: isn’t there a part of us all just craving to be told that the work we have produced is genius? Before surrendering your manuscript for review, interrogate your motives. Consider who you are asking to review your work and what you are asking of them. If you are unwilling to receive criticism or act upon it, set your manuscript aside or submit it for publication.

Your thoughts

Was there a mentor who helped you overcome adversity or gave you faith in yourself? Was there an experience that altered your approach to writing or reading? Do you have advice to share? Drop me a line in the Comments box below or . I would really, really love to hear your experiences.

way on a yacht; naturally I was wondering what the heck I was doing and what awaited me on the high seas. Somewhat unexpectedly, the palm reader told me I would live surrounded by cows. Naturally I dismissed him as a phony but in fact he turned out to be right. Ever since I have been surrounded by cows — up in the Whitsundays for ten years and now down here in Bega on the far south coast of New South Wales. When I look up from my

way on a yacht; naturally I was wondering what the heck I was doing and what awaited me on the high seas. Somewhat unexpectedly, the palm reader told me I would live surrounded by cows. Naturally I dismissed him as a phony but in fact he turned out to be right. Ever since I have been surrounded by cows — up in the Whitsundays for ten years and now down here in Bega on the far south coast of New South Wales. When I look up from my JS: Oddly enough, when I was about twenty I woke up one morning with the thought in my head that I was going to be an editor, even though I didn’t have the first clue what an editor did. I was at uni in England at the time and the careers adviser laughed at me and told me I should become an accountant. Thankfully I came to Australia instead because I have the sneaky suspicion I would have ended up in jail for embezzlement. In Sydney I sent out my cv to every publisher in town, still completely ignorant of what an editor did. Thankfully James Fraser, then the publishing director at Pan Macmillan, offered me a job as his secretary. Whilst I was proving myself incompetent at that I was given the opportunity to read through the slush pile and then eventually to learn from two very skilled editors – Jane Palfreyman and Fiona Giles – who gradually trained me up into an editing role.

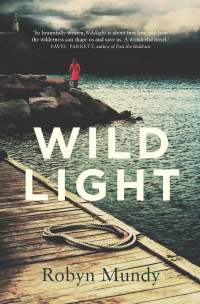

JS: Oddly enough, when I was about twenty I woke up one morning with the thought in my head that I was going to be an editor, even though I didn’t have the first clue what an editor did. I was at uni in England at the time and the careers adviser laughed at me and told me I should become an accountant. Thankfully I came to Australia instead because I have the sneaky suspicion I would have ended up in jail for embezzlement. In Sydney I sent out my cv to every publisher in town, still completely ignorant of what an editor did. Thankfully James Fraser, then the publishing director at Pan Macmillan, offered me a job as his secretary. Whilst I was proving myself incompetent at that I was given the opportunity to read through the slush pile and then eventually to learn from two very skilled editors – Jane Palfreyman and Fiona Giles – who gradually trained me up into an editing role. JS: I love your description of the editing of Wildlight and that was exactly what I hoped for. More than anything I want a writer to learn to trust themselves – as you say, to feel empowered to trust in their own creative capacity. It’s very satisfying when an author says, yes, I knew that wasn’t quite right but I didn’t know how to fix it, and then, simply through the process of having their manuscript reflected back to them, they find exactly the right solution. This is a very enlivening process, for them and for me.

JS: I love your description of the editing of Wildlight and that was exactly what I hoped for. More than anything I want a writer to learn to trust themselves – as you say, to feel empowered to trust in their own creative capacity. It’s very satisfying when an author says, yes, I knew that wasn’t quite right but I didn’t know how to fix it, and then, simply through the process of having their manuscript reflected back to them, they find exactly the right solution. This is a very enlivening process, for them and for me.