I am officially an Australian Detainee, partway through a second round of hotel quarantine. Twenty-eight days to make sense of a voyage to Antarctica and South Georgia that wasn’t, except for five halcyon days exploring the Antarctic Peninsula. Innocents were we in that realm of ice and wilderness, to the maelstrom ahead.

BEFORE

Listen. Listen. Heed your intuition.

MV Greg Mortimer steams away from the port of Ushuaia in Tierra Del Fuego, four days after the World Health Organisation ‘characterises’ Covid-19 as a pandemic. Covid has shaped itself into a character, wreaking havoc through its own dystopian novel.

This is my 23rd year of working in the polar regions north and south. I live a blessed life, astonished that as I grow older, opportunities have increased rather than diminished. I work hard. I believe I am good at what I do. In the week before leaving home, Covid consumes the ABC News, The 7:30 Report; Dr Norman Swan’s steadfast bats a louder, longer volley of science and statistics. I try to recall the very first news mention of a Wuhan ‘seafood’ market, as it was in that first iteration, where a group of workers presented with lethal flu-like symptoms. I remember less about the words than the prickling that charged across my skin.

The plight of Diamond Princess is all across the news. I think to my voyage ahead. I do not want to contract the virus, but my anxiety lies more in being stranded, unable to get back home. On advice from a friend I head to my GP in those final days at home for a precautionary pneumococcal vaccination. Dr Sarah asks about the ship work, how I’m feeling. ‘Do you have to go?’ she speaks to my unhappiness. ‘If I don’t,’ I answer, ‘I’ll be forcing someone else to take my place.’ That is one truth. The noble truth. I love what I do. I also need to earn the income. And if I forfeit my contract so close to departure, never mind my track record, chances are I will not be asked to work again.

Off I go.

Life eases on arrival in Ushuaia, el fin del mundo as the town prides itself, a picturesque southerly port that in my two decades of coming here has expanded seven-fold on the shoulders of Antarctic tourism. In this once-frontier-now-overpriced-tourist town, the air feels crisp and clean. Remnant snow clings to the surround of peaks. It is a beautiful place. I walk along the foreshore soaking up the southerly air. Familiar territory. The start of any happy voyage.

Sunrise over Ushuaia and the Beagle Channel, embarkation day, 15 March 2020

On embarkation day our outgoing ship’s doctors visit hotels to ensure the good health of our incoming passengers, taking temperatures, checking for flu-like symptoms, scouring the relevant travel history of each person who boards the ship. Would-be passengers from high-risk regions have already been declined from joining the voyage. Ninety Australian passengers, 12 New Zealanders, 12 from across the UK, Europe and USA. The expedition team makes up a further eighteen, with Florence as Expedition Leader, me as Deputy Leader. The ship’s crew, 85, are from all over, many from the Philippines. We are a small expedition ship. A low risk group of travellers. We are nothing like Diamond Princess. Why, then, when I step aboard does it feel like a game of Russian Roulette?

Lifeboat and safety drill is a maritime requirement before leaving dock

As we ease away from the dock, I would like to remember a bubbly, happy ship, raring to go. But we are not. Not entirely. Several passengers express fear and anxiety. I listen. I am careful not to say, everything will be okay. I do not say, we will be just fine. I visit one couple whose outright rage stems from feeling trapped. They do not want the voyage to proceed. What if I had said to them, Heed your intuition. Go home. Go home.

Others onboard sparkle with the thrill of a trip of a lifetime. Antarctic Peninsula, Elephant Island, South Georgia, the Falklands. We are on our way, east along the cold waters of the Beagle Channel, seabirds skimming by. Argentina to our portside, Chile to our starboard.

We pass the distinctive silhouette of Mount Olivia which each time brings to mind a junior passenger from long ago. Your mountain, young Olivia. The road gives way to tracks. Tracks merge into forests of beech. It turns midnight when the first roll of ocean lifts our keel. We forge out to open sea.

DURING

a cage is a cage

Day 2: 16 March 2020: New Zealand announces that its flagship airline will suspend long-haul flights from the end of March. A whisper comes down the line: Ushuaia may soon be set to close its doors. The inevitable penny drops sharp and shrill. The ship quavers with an image of one then the next airline shutting down, borders snapping shut. The company heeds our grave concerns. But Ushuaia closes its borders and we can no longer simply turn around. A decision is made to shorten the voyage. We must do our time at sea, our own personal quarantine.

Day 3–7: 17–21 March: Arrangements are underway for an end-of-month charter flight from Stanley in the Falkland Islands, the lag of days between now and then ensuring we can safely dock and pose no risk, confident in everybody’s eyes that we remain a healthy ship. We are a healthy ship. Not a hint of a cough or cold. We forgo our beloved South Georgia and beeline to the Antarctic Peninsula, intent on sharing with our passengers this beautiful, extraordinary, crystalline corner of the planet. With all but one other ship having departed the Antarctic Peninsula, we revel in choosing our favourite sites. These are precious, joyful days. To be here virtually alone feels both extraordinary and eerie, a time warp back to my first 1996 voyage when to see another ship was truly an event. We soak up five blissful days: icebergs, penguins, whales. We steam past countless glaciers and rug up out on deck to take in the surrounds. Each new day delivers something special and wondrous.

Juvenile gentoo penguins at Danco Island

Steam rises from the volcanic shoreline of Whalers Bay, Deception Island

Left to right: Thérèse Horntrich (Assistant Expedition Leader, Switzerland), Florence Kuyper (Expedition Leader, The Netherlands), Robyn Mundy (Deputy Expedition Leader, Australia).

Lemaire Channel. Nearby Port Charcot is our southernmost landing.

Day 7: 21 March, evening: We leave the Peninsula, northward bound. Seven days have passed. Seven. My Covid guard eases. Everyone is well. I feel the shroud of concern slip from my shoulders. We have squeaked through unscathed. We are safe. Surely.

Day 8: 22 March: I sit in the front corner of our lecture theatre as one from our team delivers an Antarctic presentation. From behind and all around me I listen to a dissonance of small dry coughs. I look to Expedition Leader Flo at the very moment she looks to me. Perhaps we both close our eyes in the same ragged breath.

In the early evening our ship’s doctor shares with us that a passenger has just presented with fever. The patient and partner have been moved to the ship’s isolation wing prepared in advance for this unwanted reality.

Day 9: 23 March: Lock down. Our passengers are confined to their cabins where they will remain, heroes, troopers, each and every one of them, for an interminable 19 days. We do not know the cause of the fever. Until proven otherwise we must prepare for Covid while we hope against hope for a better outcome. The cabins are spacious and beautiful, heated bathroom floors, big screen tv’s, nearly all have their own balcony. This I know: no matter how you dress it up, a cage is a cage.

Day 10: 24 March: We are a ship with fever. Borders close to us. We say goodbye to the prospect of Stanley providing us a Cordon Sanitaire from the dock to a plane. We set a course for Montevideo, the capital of tiny Uruguay whose port remains open. We fang northward at 14.6 knots, pushed along by the might of the Falkland Current. Wanderers, Black-browed albatross, small and large seabirds wheel by, soaring in the winds.

Daily temperature testing

Day 11–13: 25–27 March: Our two ship’s doctors don and doff full PPE gear to conduct twice daily temperature checks of every person aboard. More fevers emerge. Some present without fever, just mild symptoms from headache, scratchy cough, diarrhoea, changes in taste and smell, general achiness, to feeling a bit off. One doctor is convinced of Covid. The other has his odds staked on a less insidious ship’s bug. We in the team grow to mistrust our bodies: we fret about a sneeze, a clearing of the throat, a tightening of the chest. In bed at night I check my brow with the back of my hand, convinced it is warm, relieved the next day when the doctor’s thermometer flashes a healthy number. Dr Mauricio has an uncanny habit of leaping unannounced into our office doorway, his thermometer primed. ‘¡Hola, Senoritas!’ He makes us laugh.

We are a unified, harmonious team, kept strong by the remarkable spirit of Florence. We are also supreme at adapting. After all, on any given day in Antarctica, plans change, determined by the vagaries of weather. Regardless of our official shipboard roles, we are willing participants in whatever needs doing.

Meal deliveries set down outside cabin doors

The days of isolation fall into an ongoing pattern of washing hands countless times, donning masks and gloves. These are in short supply and we are compelled to wear this gear for days at a time. We deliver three meals a day to outside cabin doors. I make the wake-up calls, give announcements through the day. Flo speaks at length to the ship at least twice each day. There is no spin. No bullshit. We tell it as it is, even when there is nothing new to say.

Meals in the dining room

Daily, the team phones each cabin for a catch up, checking how each passenger is faring within themselves. It becomes a very nice way of connecting. We man and woman the reception phone to give the last standing crew receptionist her breaks. We take afternoon cappuccino orders and rotate the tasks between us. Swiss Assistant Expedition Leader Thérèse creates the daily ‘rooster’ as she calls it. We love her Swiss variation and adopt it as the roster’s title. I discover I am a better Zodiac driver than balancing a heavy dinner tray up and down the stairs. The friendly dishwasher in the galley never loses his patience at having to rinse my tray of spills. The dining room is stripped of its finery. We in the team eat our meals one per table, too far apart for easy conversation. Historian Carol likens us to Benedictine monks, alone with our supper in silent reflection.

We publish The Masked Penguin, a simple news sheet the mono printer churns out each morning. We mask up to offer daily broadcasts over the ship’s intercom. Alan our Canadian seabird naturalist enthuses us with new birds outside our cabin windows. Jane our kiwi mountain guide offers cabin workouts. Aussie kayaking guides Daniel and Eamon deliver Q&A sessions, comprising genuine and goofy questions. They read from a selection of passenger haikus: Sunlight glistening / Reflecting through the window / Our thoughts shimmering

Our host of team experts speak about weather and climate. They recount anecdotes from former lives as Antarctic research scientists and field assistants. Dan develops quite a following and we joke that when all this is over he has a second career waiting in radio. The speakers in the ship’s public areas overheat with the spikes of activity and threaten to fail. We adapt our broadcasts.

Day 13: 27–31 March: We arrive at Montevideo on the evening of 27 March. We anchor out in The Roads, 12 nautical miles offshore. This will be our home for the next 14 days. Passengers in portside cabins look down from their balconies at a school of hammerhead sharks cruising by.

Montevideo sunrise

Uruguay supports us with provisions and medications. When the shallow waters of Rio Del Plata grow turbulent and too stirred with mud to make our own fresh water, a supply vessel tops up our supply. My newly washed hair feels as coarse as straw. ‘Do you think it’s Covid?’ I say to Flo. She checks her own hair. ‘If it is, we both have it.’

We are not permitted to berth at Montevideo until our ship remains fever free for 14 days. With 217 aboard and a rolling infection, the quarantine clock winds back to zero each time a new fever presents. Mountaineer Jane calculates we will be free to berth in approximately two years.

Cargo ships and bulk carriers sit at anchor in The Roads, each waiting their turn to go alongside. Our immediate neighbour is a ship from the Greenpeace fleet. On the other side MS Expedition sits at anchor with only crew aboard. She was destined to leave Ushuaia for Antarctica around the same day as us. Her voyage was suspended, her passengers sent home, the risk to lives deemed too high. I picture the crew looking across to us with empathy, their decision validated.

Day 17: 31 March: I will look back on this day as the moment when Covid morphed into a sinister new being, capable of indiscriminate assault. A male passenger with fever develops acute respiratory problems and is medevaced to Montevideo’s Hospital Britanico. It will be the first of many mercy visits from Uruguay’s SAR vessel which motors out in rough sea conditions to collect unwell passengers requiring hospitalisation. We are so very grateful for Uruguay’s medical support. With both vessels side by side, heaving in the swell, our first patient, dressed in full PPE gear, steps across the abyss from one vessel to the other, the SAR crew gripping the railing with one hand, waiting to catch him with the other, the oxygen tank still attached, thrown across in his wake. I cannot decide who is the braver: our passenger or that Uruguayan crew.

Dr Mauricio Usme

Day 18: April Fool’s Day: Through this entire time our ship’s doctor Mauricio, the undeniable hero of the voyage, has taken the front line and with it the very great risk of contracting the virus. His strategy is to protect our second doctor should he, Mauricio, fall ill. Dr Jeff is wakened in the night. Mauricio is running a high fever and has isolated himself to his cabin. Dr Jeff’s worst nightmare has arrived. He attends to Mauricio then assumes sole medical responsibility.

We wait for test results to come back from the hospital where our first patient is now in a critical condition in ICU. I wish I could hug his partner who remains onboard alone in her cabin. A female passenger in cabin isolation takes a turn for the worse. More from our ship’s crew succumb to fever. Two by two, crew and cabin mate retreat to isolation.

The test results arrive. That it reads Covid should be no surprise and yet we hang our heads. We, this ship, this blighted voyage, we are the April Fool.

Florence, Captain and I hold an emergency meeting. With the current trajectory, we calculate the obvious: already there are not enough stewards to deliver meals; we in the team have been working to fill the growing shortfall. Soon there will be insufficient crew to cook and prepare meals, to maintain a sustainable level of hygiene around the ship, to fulfil the vessel’s technical requirements, to even man the bridge. Captain transmits the message to the Uruguayan Coastguard: We have reached a humanitarian crisis. We are in need of urgent help.

Day 19: 2 April: Wild seas prevent the rescue vessel from motoring out to retrieve unwell patients.

Day 20: 3 April: The wind is still strong, the ocean still rough. The rescue vessel tracks back and forth to collect two ill crew members and another passenger. In the evening a vessel brings a team of young Uruguayan medics who board the ship. I wonder if they might be medical graduates or even students who have volunteered for the task. They work seven hours straight, half the team going from cabin to cabin to test passengers with a PCR nasal swab, the other half working in the mudroom to test each of the crew and our team. As the ship heaves in the swell they perform each swab. It is midnight before I am close to being tested. I watch crewmen leave the testing bench, pinching the bridge of their nose, shaking off the sensory assault of having a swivel stick poked far up each nostril. The medic speaks in gentle, broken English: ‘Do you mind if I take a moment? Fresh air.’ She gestures to a side door. I recognise seasickness behind that face shield and mask. Within minutes she returns to her post to perform my test. I leave the mudroom gripping my nose.

Day 21: 4 April: Dr Jeff falls to the virus. A Uruguayan doctor comes aboard to stay and assist. He works hard. He speaks no English. Naturalist Roger helps to translate.

Day 22: 5 April: A Uruguayan medical team comes aboard and spends most of the day doing medical check-ups for everyone onboard: temperatures, blood pressure, blood oxygen, questions about symptoms. We are told informally that a high proportion of the ship’s company has tested positive for Covid. We are not given numbers. Test analysis is still ongoing at the lab. The team gives some of us our individual test result.

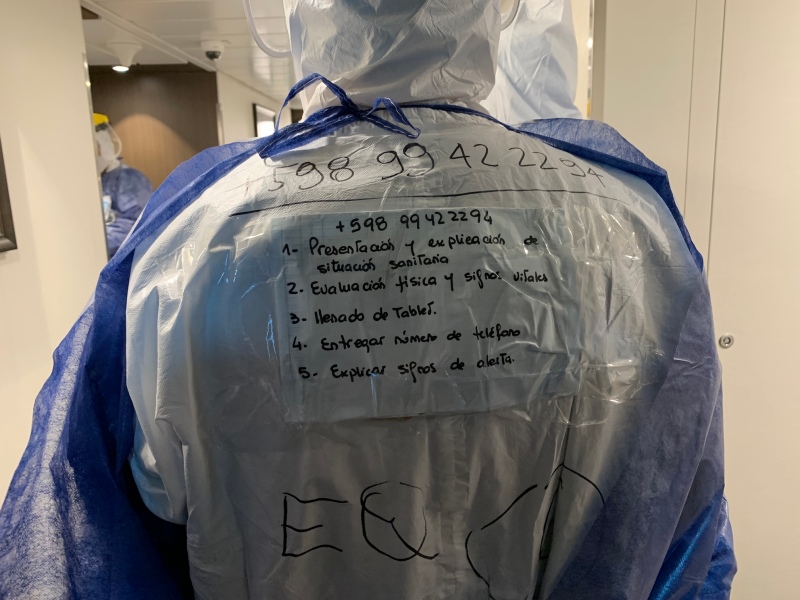

The Uruguayan medical team show us the number to call should we present with symptoms

Day 23: 6 April: The full test results from the PCR nasal testing are emailed to the ship. Results are shared amongst the crew’s senior managers though not with our Expedition Leader. Printouts showing each person’s results are left on the bar and in the public lounge. Our mountain guide learns his results from the Hotel Manager. What of medical confidentiality? We learn that sixty percent onboard have tested positive to Covid. Fear sets in amongst those in the crew who test negative. Our passengers, safe inside their cabins, remain oblivious to the shift in mood aboard the ship.

Days 24–25: 7–8 April: Our days grind on, the company working around the clock to negotiate a medical charter from Montevideo to Australia, another to the USA and on to the UK. Throughout these days, each new charter possibility, each new negotiation with Consulates and Ministers, has been dashed. We know our company is scouring every avenue to get our passengers and team home, but this rollercoaster is a cycle of hope and despair. Today we are told, cautiously, that things are getting close, that we are at last on the verge of a very real outcome. Contracts with charterers, agreements with governments, are being drawn up, ready for signing. Each morning we print out copies of a new daily update from head office and post it outside cabin doors. I remove the company logo from all but the front page to cut down pages. We are down to our last box of paper.

Day 26: 9 April: Arrangements are firmed up for a medical charter flight to Australia. The kiwis will join the fight then transfer to a small charter direct from Melbourne to Auckland. Tomorrow at 0500 a specially fitted Airbus A340 will arrive in Montevideo from Portugal. We are told that the charter specialist has been operating for 15 years, repatriating passengers and transporting vital medical and protective equipment around the world. It feels like a miracle in the making. A gripping ride arrowing to the sky. I dare not set my hopes too high.

Day 27: 10 April: I wake from a dream that we are stopped on the road by angry protestors. I arrive at the ship’s office to learn that the charter plane has touched down on schedule. It is here, really here, waiting for us at Montevideo’s Carrasco International Airport. Uruguay has agreed to provide the 97 Australian and 15 New Zealand passengers and team members a Humanitarian Corridor from the dock to the airport. I have butterflies in my stomach that flutter stupidly for the entire day. Let it happen.

As I announce the day’s plans and details for the flight, the moment grows bittersweet. Our internationals. We are leaving twelve passengers and eight from our team behind. Their arrangements are still to be finalised. Worse, the atmosphere onboard has escalated into one of volatility. While Florence makes plans to protect her remaining team, arranging their move to adjacent passenger cabins with adjoining balconies, I inform the Australians and New Zealanders of our flight arrangements. We may bring only carry bags. We must leave our check-in luggage behind. No exceptions. No baggage handler will handle our contaminated luggage. Yes, we may bring scissors, sharp objects, no limit on liquids, so long as we alone can carry our belongings to the plane.

I believe all of us would have walked onto that plane with nothing.

The day is hectic. Late afternoon arrives before I focus my sights out the windows. The city of Montevideo shimmers silver, the skyline no longer a distant haze but a distinct line of buildings new and old. ‘Are we moving?’ I state the obvious. Normally I would be on the Bridge, looking forward, but the Bridge has been closed to all but ship’s officers since the first fever.

As we approach Montevideo Harbour, people are lined along the shoreline. They stand on the sea wall. It takes me a moment to register the full meaning. They are waving. They cheer and hoot. They look so happy to see us. They are not here to protest or turn us away. I step out onto the open back deck to wave back. To cry. Uruguay: you are a small country with a big heart. Locals post photos of our arrival to the company’s Facebook page. They text dozens of messages. ‘You will be home soon. You will be safe.’ ‘Uruguay loves you.’ ‘We welcome you, dear friends.’ They are humanity as its most generous and inspiring.

At 2130 we call our first passengers down. It feels strange to see these faces after 19 days. As if we are meeting for a first date, unsure of how to be with one another in this new, socially distanced world. Each person is donned in gloves and an N95 mask. Buses pull up one by one. Passengers are counted off as they make their way down the gangway. All but two of our passengers from hospital will travel by ambulance directly to the plane. Our two who remain in ICU are deemed not yet strong enough to travel. Their partners are transported from the ship to the hospital to remain behind and be by their sides.

The 45-minute journey from the dock to the airport is a spectacle, even from the inside of the bus. We are a kilometre-long cavalcade of buses, security vehicles and ambulances. Later I will watch images of the event on Uruguayan television news. For now, coloured lights flash. Sirens blare. On every corner of every street a parked police car or motorbike halts local traffic. It is difficult to see through the darkened windows of the bus. I make out people on sidewalks, standing on balconies. Arms are waving. Flags fluttering.

HiFly Airbus A340 charter plane at Montevideo airport

This is no regular airport check-in. Each bus in turn moves out onto the tarmac beneath the wing of the enormous Airbus. I have never seen such an aircraft from this perspective or understood its full height. In slow orderly procession we make our way up one of two very steep outdoor steps and directly into the plane.

The cabin crew are dressed in white hazmat suits, hoods, goggles, masks and gloves. In my section the attendants are nearly all men, Portugese names written on their suits in black texta. They greet us warmly, as if we were any regular traveller returning home from holidays. Areas of the cabin are cordoned off with plastic sheeting to create medical bays. It resembles a scene from Breaking Bad, akin to a makeshift meth lab. Doctors and nurses are onboard to attend to our hospital patients and any traveller needing assistance during the 16-hour nonstop flight. I have been tasked with handing the ship’s ‘Fit to Fly’ document to the pilot. The plane, I have been told, cannot leave without it. The signed, stamped document lists each person’s health status and body temperature, final recordings taken onboard that afternoon. The cabin attendant I talk to seems puzzled by the documents. He takes the envelope and sets it aside. I go to urge him how vital it is that these papers reach the pilot. I stop myself, take my first steps back from my shipboard role. The crew, now, are in charge. Attendants show us to our seats and sort out mix ups, they soothe anxieties, help stow bags that no longer fit the crammed overhead bins.

There is no dilly dallying. We push back the moment the doors close. I do not register a safety demonstration though perhaps sensory overload is at play. At 0145, right on schedule, we move into position and in a mighty surge and rumble we barrel down the runway, arc up into the sky. We are away. Above the city. Tracking west across the night.

I wake at predawn as we cross the beautiful New Zealand alps. They feel as comforting as home.

Crossing the Australian coast

When I wake the next time the wing of the plane is enveloped by apricot sunrise. We cross the Australian coast. The pilot’s voice comes over the loudspeaker to thank us for choosing his airline to travel with. He hopes to see us again. Under better circumstances, he adds.

At 0655, Easter Sunday morning, we touch down on the tarmac at Melbourne.

The Airbus on the tarmac in Melbourne

AFTER

a league of tragedy

On 15 April 2020 our internationals take their turn on a Boeing 737 medical charter to Miami, USA. From there follows an elaborate series of smaller charter flights which, miraculously, thanks to the company’s detailed arranging, all line up. The exception is our Canadian naturalist whose final charter is redirected mid-flight due to a refusal to the plane to land in Canada. He is met by ground ambulance and driven the final hours to the Canadian border. The ambulance doors open to a line of uniformed border guards wearing surgical masks and guns in their belt holsters. He asks them, ‘Are you here to shoot me if I make a break for it?’ A moment’s silence before they break into a grin. ‘Welcome back to Canada.’

The 737 continues on to the UK, to ground ambulance shuttles, to yet more charter flights onward to Europe, all the 19 delivered home.

Partway through my Melbourne quarantine we receive news from the ship that Ronnie, a Philippine crewman, has passed away from Covid. Since being admitted to ICU in Montevideo, his health status has remained confidential. The news leaves us numb with shock. The voyage plunges to a league of tragedy.

As I sit here in Hobart quarantine, the ship remains at anchor off Montevideo. Two of our passengers remain ashore in Hospital Britanico, supported by their partners. Our Zodiac Manager is the last of our expedition team still aboard, our company working through the challenges to repatriate him home to Russia.

Eighty-four crew members from numerous countries are still on board. Some have been separated from their families for close to eight months, having signed on in September 2019, a time before Covid-19, when the newly built ship departed its Chinese shipyard.

After a stint in hospital Dr Mauricio is back onboard, thankfully fit and well. He remains a strident voice in appealing to the USA-based company which employs the crew, and to the Uruguayan government, to repatriate the crew to their homes.

I would not wish this blighted voyage on anyone. Yet even owning my premonitory fears leading up to the voyage, I do not regret being part of it. To witness the courage and stamina of our passengers, and to work with a remarkable team of resilient, capable, rock-solid colleagues who each laid their life on the line, was a privilege. Equally, it was a joy to work side by side with an exceptional expedition leader who recognised and drew upon every person’s strengths. I like to think we shared fortitude, clear thinking, compassion and caring, qualities that help get us through.

Touch down in Hobart, Tasmania

Photos and text ©Robyn Mundy, 2020

News articles relating to the voyage and current situation aboard can be sourced from the following hyperlinks:

3 May 2020:

21 April 2020:

21 April 2020:

Dr Alan Burger (shipboard naturalist) website and blog:

Hi Robyn,

Thank you for sharing your experience. It has taken me days to read the article. I had to stop several times as I was overcome with emotion. Tears are still flowing down my cheeks. My heartbeat is racing and my breathing laboured. I’m not ill though. I am a passenger who was aboard the ‘Ocean Atlantic’ sailing at the same time as your voyage. The memories are obviously rawer than I thought. We waited patiently for word of the GM sailing up to Rio del Plata, hoping you would all be joining us on the charter flight home. We waited patiently each day to see the ship dock alongside ours. The GM didn’t arrive. We then found out why. We saw the ambulance waiting on the dock to transfer one of your passengers to hospital. After passenger action on our ship finally secured a charter flight for us from Montevideo to Sydney, we were devasted to learn on arrival of your plight. Many of us corresponded with a couple of your passengers and more of their family members and were so pleased to be able to provide support and information from our experience. Uruguay has a very special place in my heart as we also had friendly waves from the people of Montevideo. The Port and airport staff were so helpful and kind.

My journey continues now home.

LikeLike

Hi Meryl, Whew, what an ordeal you went through. I did see a news clip while we were aboard of a politician aboard OA who was appealing to the Australian government for assistance in facilitating the repatriation. There were false starts for both ships in that effort. What a stressful outcome to what should have been a magical voyage. You must have been so happy and relieved to get home.

Thanks for your response to my article. I can well imagine it would have stirred up emotions, and will continue to do so in the aftermath. Take care—Robyn x

LikeLike

This is an amazing story, Robyn. Here in Oz, we heard only snippets about the ship stranded off Uruguay with sick Australians onboard, so thank you for documenting and sharing your diary with us. Good health to you. 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you, Louise. It’s good to be home. 🌞

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much for sharing your harrowing personal experiences on the MV Greg Mortimer, we found that reading your Post was a very emotional experience for us. Your beautiful writing drew us into the experience so much that it was almost as if we had been there, so had to wait a couple of days before writing this reply. We did the Jewels of the Arctic voyage in August 2016 when you were the Assistant Leader & read your books & have been reading your Posts on Writing the Wild ever since.

Tony & I had sailed on the Polar Pioneer with Greg Mortimer as Expedition Leader in January 2002 (which was a truly wonderful 21 days experience) & had wished we could do that very same voyage on the new ship named after him; we felt very sad when we heard & saw the reports on TV after the ship’s arrival in Montevideo.

We wish you all the best in the future and hope to read on your next Post about a voyage that was filled with halcyon days.

Kind regards

Vivienne & Tony

Vivienne Nielssen & Tony Roark

LikeLike

Dear Vivienne and Tony,

What wonderful and now poignant memories of our beloved Polar Pioneer. Thank you for your thoughtful email. It is so very difficult to see a ship bearing Greg’s good name associated with misfortune. Greg and Margaret created outstanding opportunities and life shaping moments for so many adventurers. Thank you so much for your support in following my website and reading my work. I hope to see you again on the high seas some fine, Covid-free day. 😊🛳⛴⚓️

LikeLike

Robyn…Your account is electrifying and beautifully written. We were just saying yesterday that this all seems like a dream from which we just can’t wake up, but what you have described is a dream voyage that turned into a true nightmare. Wishing you well, Ellen and Gary

LikeLike

Thanks Ellen. Our passengers were such heroes throughout their confinement. It was very tough on them, and challenging for everyone else aboard.

LikeLike

Hi Robyn

So pleased you are back home in Tassie again. What an incredible experience and difficult for everyone. Am sure as always on the Aurora trips you have been a tower of strength to all..our trips on the Professor Molchanov and Polar Pioneeer were highlights in our lives so am sure The Greg Mortimer will provide special memories too.. Covid19 has certainly changed this world we live in.

Take care, stay well.

LikeLike

Hi Reay, we all go back a long way with those two marvelous little Russian ships. It was such an incredible era of polar adventure travel. I hope we cross paths again on the high seas. Warm wishes to you both. Robyn xx

LikeLike

I am so grateful to have stumbled across your account of this experience. It was shared by a friend on Facebook. I felt so much emotion reading it. One of my dear friends was aboard the Mortimer at this time. We are yet to be able to catch up in person . He is in self isolation and very luck to have not contracted COVID. My friend briefly spoke to me of the Incredible kindness displayed by the People of Uruguay and deep sorrow for the loss of Ronnie. Thank you to you and your crew for your courage and strength. Are you ok?

LikeLike

Thank you for your words. It will be wonderful indeed to catch up with your friend in person. He has certainly been through an ordeal. 🌞

LikeLike

Hi Robyn,

I’ve read this post with bated breath. I remember following your ship’s news, wondering how it would feel to be there. Now I know and I’m just awed by your courage, your strength and your dedication. You guys are an inspiration. Hope everything is good for the rest of the crew who is remaining onboard.

Fabrizio

LikeLike

Thanks so much for your kind words Fabrizio. It relied so much on team effort and I was so in awe of how strong, caring and supportive our expedition team proved to be. 😊🐧

LikeLiked by 1 person

My heart was in my throat the whole way through this post. We received news from the FOMI fam when the word was circulated that the Airbus would bring you home. We were all so thankful to hear of your safe return. While reading of your experiences, I couldn’t help but see parallels with the original Antarctic Expeditions, facing one harrowing challenge after the next. Then again, rather than being at the mercy of your own 2 feet to keep you moving, you were trapped where you were. And further still, expected to be hospitable through it all. I truly cannot imagine the conflicting emotions you must have felt when you were leaving that ship, the sorrow for having to leave shipmates behind and the gratitude for going home. You are a warrior that is for sure. In heart and in mind. I imagine you’ll have had your share of hotels after all these quarantines. Wishing you condolences for the loss of shipmates and friends. With love and warm regards, Taylor

LikeLike

Greetings Taylor,

Thank you for your thoughts on this. During the weeks aboard when I retreated to my cabin I would check my Instagram (a novelty to be on a ship with such technology) and it gave me solace to look at posts like yours, to see the natural world, to see people enjoying and revelling in normal lives. It was a great reminder of the simple joys. You are right about hotels. If there are any lingering after effects it is likely to be that I will never again want to stay in a hotel. Hand me a tent! 😁 Take care of yourselves on beautiful Three Hummock!

LikeLike

Welcome home Robyn. Even if you are confined to barracks, you’re safe. I hope you are back in Hobart. How telling it was there were Uruguayans lining the port to send you greetings of kindness and compassion while trolls in Australia pasted Facebook with unkind posts lacking in compassion. Not all, of course, but the theme was so strong. This is another beautifully crafted post from a wonderful writer. Take care and love to Gary.

LikeLike

Thanks Lynette. I understand that emotions would have run high here in Aus, especially on the heels of Ruby Princess. Uruguay captures my heart for their courage and kindness. Thanks for your very nice authorial praise. 🙏

LikeLike

When I started reading this journal I thought “no, everyone’s symptoms were coincidental to Covid symptoms – surely not Covid?!” But it was – you were a floating sick ship – How awful. However, I do know everyone would have been ‘glad’ if that’s the right word, you were there with your cool head and caring spirit. Bless you Robyn. And besides all that, beautifully written. I need to go and hug a friend now – albeit an air-hug. 😝

LikeLike

Good on you, Rosalie. Thanks for your words. As for hugs, this time of distancing has really illustrated just how necessary it is to hug and be hugged. 🙏

LikeLike

Dear Robyn

What a moving account of your ordeal, told with grace and humanity, juxtaposed with serene images of icebergs and penguins. I wish you well.

LikeLike

Thank you, Colleen for your interest, and for you very kind words.

LikeLike

Hi Robyn, What an experience. I followed your saga every day from the safety of my Maleny mountain home.

Cheers Dale Dale Lorna Jacobsen PO Box 456 Maleny Qld 4552

>

LikeLike

Thank you, Dale. Maleny sounds like a top place to be as we pass through these fragile times. Stay safe.

LikeLike

Beautiful writing, Robyn.

Thank you for having captured this ordeal for us to get a better understanding of those long days of ‘not knowing’.

We had been on the GM, disembarking on 4 March and I certainly felt we were on the safest place on the planet. How quickly all that changed.

My heart goes out to those still in limbo, either in hospital or still on board.

‘Zodiac’ Sergei had spoken to me with great excitement about the prospect of seeing beaches and palm trees on the cruise following the one you were on- was it to Costa Rica?

He told me he had never been anywhere warm in his life. I hope he gets there (one day), although he’d no doubt be more than happy just to return to his family.

Wishing all those still on the GM a safe and swift return to their homes.

LikeLike

Thank you for your thoughts. I imagine you would have had a wonderful voyage to Antarctica and then returned to a sobering new world by 4 March. Things were quickly ramping up. The good news onboard is that late last week all but a skeleton crew disembarked ashore in Montevideo, and are now in quarantine at hotels. Hopefully this marks a big step in their journey home. Thanks for checking in and may those memories of ice and penguins stay with you forever. 🐧🌞😊

LikeLike

Dear, dear Robyn

My first inkling that anything was amiss came from a friend who was on GM on the early January voyage.

I am so relieved that you are back safely on Australian soil. You have been in my thoughts constantly the past couple of months, wondering if you were well. It must have been horrible seeing so many of the passengers falling ill and I was saddened that one of the crew lost his life. As you have found out the ramifications of COVID-19 are huge – and horrifying. I wonder how people can remain sane in such a topsy turvey world. You are such an amazing lady.

Take care of yourself and I hope you can get back what you do best as soon as you can. At this stage I am quite concerned about the Christmas voyage. It’s a waiting game.

Warmest wishes to you both

Vi and Michael

LikeLike

Hi Vi and Michael

We have had some special times together on Polar Pioneer. The “before” era I now think of it. It is hard to know how life will look for companies and ships such as Aurora’s in the “after” era. Thank you for your kind words. Stay safe, dear Vi.

LikeLike

Amazing story, thanks Robyn, for enduring this nightmare and finding the energy to write about it

George Clark

LikeLike

Thank you, George. It makes our memories of Polar Pioneer even more sweet and poignant. I hope you are both keeping safe and well.

LikeLike

An amazing experience, Robyn, surely a worthy contender for the life-changing category. And your calm grace shines through, as always. Thanks for sharing this. x

LikeLike

Thank you, dear Amanda. And thank you for your message of support during the voyage.

LikeLike

Robyn, I shared this on Facebook and several people send you love and best wishes: Rashida Murphy, Liana Joy Christesen, Rae Hilhorst, Marlish Glorie. x

LikeLike

That’s very very nice. 😊

LikeLike