Author Annabel Smith, who I interviewed a little while back (just scroll down), has launched a new series on her website called Coming to Writing. Annabel invited me to share my circuitous journey to becoming a writer. I’ve titled it The Reluctant Writer

Tag Archives: tips for writers

Publishing: getting the word right

The Editor

JS: When I was in my early twenties I had my palm read. I was about to leave my life in Sydney and sail a

way on a yacht; naturally I was wondering what the heck I was doing and what awaited me on the high seas. Somewhat unexpectedly, the palm reader told me I would live surrounded by cows. Naturally I dismissed him as a phony but in fact he turned out to be right. Ever since I have been surrounded by cows — up in the Whitsundays for ten years and now down here in Bega on the far south coast of New South Wales. When I look up from my

way on a yacht; naturally I was wondering what the heck I was doing and what awaited me on the high seas. Somewhat unexpectedly, the palm reader told me I would live surrounded by cows. Naturally I dismissed him as a phony but in fact he turned out to be right. Ever since I have been surrounded by cows — up in the Whitsundays for ten years and now down here in Bega on the far south coast of New South Wales. When I look up from mydesk I see rolling green hills and well-fed Friesians. Actually, I try not to look up from my desk too often because a) such loveliness is distracting, and b) I might notice my teenagers running riot through the rest of the house.

How did you get into book editing?

JS: Oddly enough, when I was about twenty I woke up one morning with the thought in my head that I was going to be an editor, even though I didn’t have the first clue what an editor did. I was at uni in England at the time and the careers adviser laughed at me and told me I should become an accountant. Thankfully I came to Australia instead because I have the sneaky suspicion I would have ended up in jail for embezzlement. In Sydney I sent out my cv to every publisher in town, still completely ignorant of what an editor did. Thankfully James Fraser, then the publishing director at Pan Macmillan, offered me a job as his secretary. Whilst I was proving myself incompetent at that I was given the opportunity to read through the slush pile and then eventually to learn from two very skilled editors – Jane Palfreyman and Fiona Giles – who gradually trained me up into an editing role.

JS: Oddly enough, when I was about twenty I woke up one morning with the thought in my head that I was going to be an editor, even though I didn’t have the first clue what an editor did. I was at uni in England at the time and the careers adviser laughed at me and told me I should become an accountant. Thankfully I came to Australia instead because I have the sneaky suspicion I would have ended up in jail for embezzlement. In Sydney I sent out my cv to every publisher in town, still completely ignorant of what an editor did. Thankfully James Fraser, then the publishing director at Pan Macmillan, offered me a job as his secretary. Whilst I was proving myself incompetent at that I was given the opportunity to read through the slush pile and then eventually to learn from two very skilled editors – Jane Palfreyman and Fiona Giles – who gradually trained me up into an editing role.

What do you regard as key qualities of an effective editor?

JS: For me the most important quality is to be able to listen very carefully to a writer’s intentions. This means being able to silence your own inner voice in order to inhabit someone else’s words. When I am editing I am not trying to fix anything or to impose my meaning on the text. I’m trying to help the writer to clarify their intentions, to find those areas of the manuscript they themselves are uncertain about, and to explore and trust in their own capacity to find the necessary solutions.

It’s important, too, to be a sensitive and perceptive reader. When I first started editing I had never studied the mechanics of writing but instinctively, having read so much, I understood how stories were put together. I don’t think you can be an effective editor, or writer for that matter, if you’re not an experienced reader.

How important is the relationship between author and editor?

JS: It’s the quality of the relationship that is most important – a writer needs to trust their editor and to know that they are valued and respected. It very much depends on the individual author how significant their relationship is with an editor. I’ve worked with some very successful writers who don’t place a great deal of importance on the relationship — as long as the quality of the relationship is high, they will work with any editor; they don’t need that continuity of care and insight to produce terrific work. On the other hand I’ve worked with writers for whom a personal ongoing relationship with their editor is paramount. One author I worked with for many years said that editing was like taking her clothes off in front of someone and she was only prepared to do that in front of me! The relationship can be extremely dynamic and creative and productive, but I don’t kid myself that an author isn’t able produce great work without me.

I felt that the editing empowered and contributed to the creative strengths of Wildlight. What result do you strive for? Do you have a memorable moment?

JS: I love your description of the editing of Wildlight and that was exactly what I hoped for. More than anything I want a writer to learn to trust themselves – as you say, to feel empowered to trust in their own creative capacity. It’s very satisfying when an author says, yes, I knew that wasn’t quite right but I didn’t know how to fix it, and then, simply through the process of having their manuscript reflected back to them, they find exactly the right solution. This is a very enlivening process, for them and for me.

JS: I love your description of the editing of Wildlight and that was exactly what I hoped for. More than anything I want a writer to learn to trust themselves – as you say, to feel empowered to trust in their own creative capacity. It’s very satisfying when an author says, yes, I knew that wasn’t quite right but I didn’t know how to fix it, and then, simply through the process of having their manuscript reflected back to them, they find exactly the right solution. This is a very enlivening process, for them and for me.

Funnily enough, it’s not the moments I remember that are most significant. Often I will say something quite unremarkable and it will trigger in the writer a cascade of productive ideas. It’s not me doing the work; it’s the writer.

Does it ever happen that an author outright rejects editorial suggestions? How do you overcome differences?

JS: Actually, I’m delighted if an author thinks carefully about my suggestions and then rejects them. (If they reject my ideas without careful thought, well that’s their prerogative too.) I’m not the authority on their manuscript, they are, and if they think something isn’t going to work they need to trust their own judgement not mine. My sense is that differences tend to be minimised and are more easily overcome if you have communicated to the author the ways in which you appreciate their work. It’s easier for them to trust your response if they know you have read their manuscript with care, empathy and respect.

What might surprise the everyday person about the editing role?

JS: Perhaps that the role exists at all. People often seem to think that the writer sits down and produces the work pretty much word for word as it appears in the finished book. They’re not aware that sometimes quite a considerable amount of developmental work has been done, or that in some circumstances the editor has in effect rewritten the book.

How would you define a great book?

JS: For me there’s a distinction to be made between great literature and great books. Great literature, well, that’s endlessly debated and very much depends on your cultural, historical and personal context. A great book, for me anyway, can be defined by its impact on the reader (and it may or may not be considered great literature by other people). A great book shifts something in your internal world; it creates ‘slight inner adjustments of which we are barely conscious’ (to borrow from WG Sebald). A great book makes you experience the world in a different, more expansive way. It opens you up to life, even if occasionally that opening is savage.

Before ever submitting a manuscript to a publisher, many writers spend a lot of time rewriting. Speaking for myself, it’s never easy to switch hats from writer to self critic. Do you have advice on ways an author can approach the revision process?

JS: Give yourself time. Put the manuscript aside for as long as you possibly can, so that when you return to it, it seems unfamiliar to you. Basically this is what an editor is bringing to your manuscript – perspective. Pay attention to the small voice that tells you something isn’t quite working; invariably it’s right and what is holding you back from listening to it is weariness or boredom. When you get stuck, set the manuscript aside and daydream; walk, swim, garden, dream – do anything but try to find a solution. It’ll come eventually, often in an unexpected way.

Of course saying ‘give yourself time’ is all very well, but time is often in short supply in publishing, not to mention in our daily lives. If you have a deadline I would recommend having a clear plan for your revision process. The following process reflects the way I work; it may not suit you, so find your own way with it.

Firstly, read the manuscript from start to finish without changing a word (this is surprisingly difficult to do). Then try to think about the story as a whole. You’re looking for a general impression, as though glancing at the story out of the corner of your eye. When you come to look at it head on (that is, when you look at it scene by scene, line by line) those initial impressions will fade (or you’ll try to ignore them), but in fact they’re an extremely valuable guide. Think about which parts were satisfying, which weren’t; what didn’t make sense; where the pace slowed; which characters were vivid, which flat.

Once you’ve identified the patchy areas, go in scene by scene and try to understand how each one contributes to the storytelling, or how it holds it back. I like the technique Ford Maddox Ford and Joseph Conrad called progression d’effet: ‘we agreed that every word…must carry the story forward and, that as the story progressed, the story must be carried forward faster and faster and with more and more intensity’. Think about how those scenes might change, and what effect this will have on the rest of the novel.

When you’ve made those broad changes to individual scenes, then start looking line by line at the whole manuscript. (Yes, it’s a long process, but many writers I have worked with say they enjoy the revision process.) Read aloud to someone if you’re not sure whether something sounds right or makes sense.

It’s helpful to show your work to readers whose judgement you trust, but make sure they are prepared to be honest with you, and you are prepared to hear what they say without holding it against them.

Are you able to switch hats, to go from editor to everyday reader? Do you have a favourite book?

JS: Yes, thank goodness, otherwise one of the greatest pleasures and consolations of my life would become confused with work. I read as an everyday reader all the time but I’m very choosy about what I read and I don’t persevere with a book just for the sake of it. I have so many favourite books it’s impossible to choose only one.

Huge thanks to Julia Stiles for this wonderful interview.

Top Shelf: Annabel Smith

TOP SHELF showcases a talented writer or artist who I admire. This month I welcome long-time writing colleague and friend Annabel Smith whose personal journey I find as compelling as the novels she creates. Annabel is the author of A New Map of the Universe; Whisky, Charlie, Foxtrot (branded in the USA as Whiskey & Charlie); and The Ark. Annabel regularly chairs and presents at writing festivals.

Annabel: I always feel proud to cite you as an inspiration to writers, particularly for these two reasons: No. 1: in the time of writing Whisky, Charlie, Foxtrot, you married, became a new mother and, despite the associated joys, felt despair at ever again finding time to complete your manuscript. Tell us about the writing deal you struck with your husband.

AS: Idiotically, I had imagined having time to write each day while my baby napped contentedly. My son shattered my delusions by deciding that two half-hour naps a day were plenty, which meant that, not only could I not write in the day, but by the evening I was too exhausted to even contemplate it. So on Saturday afternoons my husband would do his fatherly duty and I would go off to the library and write furiously until they threw me out. Those three or four hours each week saved my sanity.

No. 2: When I think back to Whisky, Charlie, Foxtrot’s long…long road to publication, I cite you as the Diva of Perseverance, particularly to fellow writers who are dealing with rejection. Spill the beans on that episode.

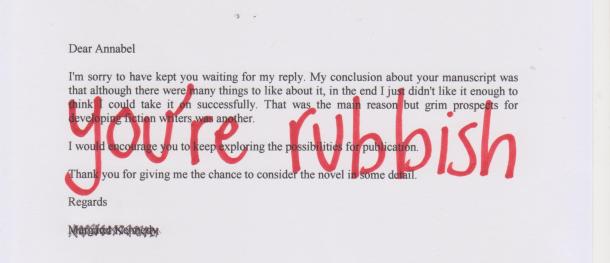

AS: Initially, I submitted the novel to agents—a dozen or so, mostly in Australia, a couple in the US and UK. On one occasion I came close to securing representation but in the end the agent was ‘not sufficiently enthusiastic’ (a phrase they’re fond of in their rejection letters). Then I began submitting to those publishers that accept unsolicited manuscripts—mostly small independent presses—collecting more rejections.

Each time I received a rejection I’d lose confidence for a while, but then I’d read a part of my manuscript and my confidence would return. If your work is good enough, finding someone who loves it becomes a numbers game: you just have to keep sending it out until you get it in front of an editor who connects with it. After 17 rejections I found that editor in . Cue: tears, champagne.

Whiskey & Charlie was subsequently adopted by a USA publisher and chosen by megastore Target as their Book of the Month. What d’you say to that!

AS: It was beyond my wildest dreams! When I received the email from my publisher to say that Target wanted to print 30,000 copies, I wrote back to check that they hadn’t accidentally added an extra zero! When they confirmed that it was THIRTY THOUSAND I was so overwhelmed I actually cried. I had to sign 5,000 pages to be inserted. (A little known-fact about mass signings is that it is not the signing arm that gets tired—it is the other arm, which has to keep taking off the signed page to expose the next one.) The market is so ginormous there. It has made me so happy to know that many thousands more readers have read my book as a result of my publication there, and I’ve had some lovely responses from US readers. To be honest, I still have to pinch myself every time I get an update on the sales figures. (Check out )

What do you most treasure about your writing life? What are you most proud of?

AS: I treasure being able to build a life around what I love—so many people do not have that luxury.

I treasure the quiet space and time alone at my desk.

I treasure the momentum that occasionally comes after long periods of hard work, when the words pour out effortlessly. Writing feels like climbing a hill (or a series of them). You climb up—sometimes energetically, sometimes listlessly, meandering from side to side, perhaps limping, sometimes the progress is so slow you feel like you’re crawling. Then, suddenly you’re at the top and the view is unbelievable, and you go charging down the other side and it all feels worthwhile.

I treasure being part of a community of writers. I have met so many lovely people—writers and readers—through writing: online, and at libraries and bookshops and talks and festivals. Book people are the best people.

I’m proud of each book for different reasons: A New Map of the Universe, because it was my first book and I didn’t even know if I could write a book; Whisky Charlie Foxtrot (branded as Whiskey & Charlie for the US market) because it was so difficult to find a publisher but I believed in it enough to persevere; and The Ark because I tried something completely new and different and I learnt so much from the process.

What kind of things pose the greatest challenges?

AS: Balancing the need to earn money with finding time to write is an ongoing challenge. I’m always trying to work out ways to earn the highest possible amount of money in the shortest possible amount of hours, so that I’ll have more time for writing; this week, for example, I toyed with the idea of becoming a foot model! At the moment I work two days a week teaching English as a Second Language to international students entering postgraduate courses at Edith Cowan University. I enjoy it a lot but i would give it up in a heartbeat if it meant I could have those two days for writing instead.

Another great challenge is rejection. As a writer, it is part of the terrain, but accepting that at a rational level and coping with it at an emotional level are two entirely different things. The writing life is an endless round of competitions—or publication, for grants, for awards, for sales, for reviews—most of which you don’t win. Sometimes it feels excoriating and I feel like I can’t bear it anymore. But somehow I always do.

Your career has progressed from a debut novel to two subsequent novels. You now have a fourth in the making (Monkey See). What I find remarkable about that collection is the breadth of imagination—four different worlds, four markedly different modes of writing and story…

AS: Two of my novels are firmly in the realist mode, whereas two have speculative fiction elements. One spans half a century, while the other three take place within compressed time periods of a couple of years. One is very poetic, the others are much less consciously prosaic; more conversational. In one we see everything from a single character’s point of view, whereas the other three have multiple narrative voices. The Ark has no real authorial voice as it is an epistolary novel, told as a series of emails, blog posts and other digital communiques. One has historical elements, one is set in the present day, one in the near future, and one in a distant future that resembles the past! I could go on, but I think you get the picture: they are all very different.

But none of these choices have been conscious. I don’t say ‘I’ve tried historical; now I’m going to write something contemporary’; I never set out to write a certain type of book. I get an idea for a story, and the structure and the voice(s) seem to make themselves felt as I begin to write. Commercially, I know it’s not recommended to write books which are all so different to each other, as many readers like authors to produce something ‘same same but different’. But creatively, the thought of being confined to a certain genre, or style is anathema to me. Doing something different with each book means I’m always learning and that’s what keeps me interested. Having said that, I do sometimes wonder why I always have to make things so difficult for myself!

Those who know you might coin it ‘an Annabel moment’—one of disarming honesty—when, as an established author, you posted your meager annual salary online for all to see. What did you learn from the flood of responses ?

Royalties $2,210

Speaking events $4,350

Other publications $500

Lending rights $260

Total: $7,320

AS: The first thing I learnt is that telling the truth about what you earn (if it’s not much) is practically unheard of, which is why it received so much attention. The responses suggested that I was far from being alone in my lowly financial position: most writers make a pittance. But perhaps my most important takeaway from that post was the realisation that it is perhaps a little entitled to expect to make a living from writing when so few people do. Why should I be different to the rest? There are many writers out there who fully expect to have to work full-time to support their writing, and the idea of being able to write for a living is a fairly modern (and mostly unrealistic) one. I explored some of the issues around why writers earn so little in .

You read a phenomenal volume and range of novels, and you regularly review them on . Do you fork out squillions on books? How do you make the time to read and review?

AS: A majority of the books I read come from the library. For the most part, I only buy books if I’m a long-term fan of an author’s work, or if I start reading and love a book so much I want to underline all my favourite bits! When I am really into a book I neglect all my other duties in favour of reading. I let my son watch TV, tell my husband it’s takeaway for dinner, and ignore anyone who tries to speak to me! I’ve stopped reviewing now. It was very time-consuming, and began to feel like a chore instead of a pleasure. Also I got into some sticky situations with other writers who took umbrage at what I’d said about their books.

As well as writing, reading and blogging, you chair writing festival sessions, to fine acclaim! Do you ever feel nervous? How important is the chair to making a scintillating festival session? What advice would you give yourself, and the author(s) you interview, when readying for a session?

AS: I was extremely nervous when I first started chairing. I felt a tremendous responsibility to give each author a chance to showcase their books as well as making sure the audience felt ‘entertained’ by the discussion. I’m not really nervous now I’ve had more practice; I enjoy it very much, and I’ve been blessed with very lovely interviewees who’ve made me feel at ease.

My mum always said ‘you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear’ and this holds true when it comes to chairing: even a first-rate chair can’t make a dull guest interesting. But a poor chair can ruin a potentially fantastic discussion (and I have, unfortunately, seen this happen many times).

The most essential ingredient for the chair is preparedness: you have to know the books to be discussed inside out. (I usually read each one twice, making notes as I go). It’s vital to craft questions that dig into the most important or interesting aspects of the books—whether those relate to origin stories, style, themes etc. After that, you just have to get out of the way as much as possible and let the authors talk.

Monkey See, your new work in progress, is at its final stage of revision. Can you give us a sneak preview?

AS: I always feel a little embarrassed when I describe this project because, even to my own ears, it sounds totally crazy. So, keep an open mind folks! It’s a contemporary take on an epic quest story, or what I like to describe as a rollicking tale of adventure!

In a post-technological future which resembles the past, the city of Santiago, Chile is in thrall to a sadistic cult which claims to ward off tsunamis by sacrificing mute children to the ocean. When a young, mute boy is captured, his teenage brother Uardo joins the cult in a bid to protect him. But after encountering Chacho, a super-intelligent, technologically-enhanced spider monkey, and his sidekick, a cocaine-addicted former scientist named Danior, Uardo realises that the only way to save his brother is to overthrow the cult before the next tsunami strikes.

Bring on the unleashing!

Finally, any words of advice to fellow writers?

AS: As a writer, it’s easy to get fixated on outcomes: finishing the book, getting an agent, getting a publisher, winning a prize, making a bestseller list etc. But, for most writers, the outcomes are not the reason you started writing; they’re simply perks along the way. The real and lasting satisfaction comes from the work itself, so I always remind myself to enjoy the process.

Visit Australian author Annabel Smith at:

Colum McCann’s Letter to a Young Writer

author of (Random House), shares some advice.

Do the things that do not compute. Be earnest. Be devoted. Be subversive of ease. Read aloud. Risk yourself. Do not be afraid of sentiment even when others call it sentimentality. Be ready to get ripped to pieces: It happens. Permit yourself anger. Fail. Take pause. Accept the rejections. Continue reading