MV Greg Mortimer

Not displaying properly? View at https://writingthewild.net

During a March 2020 voyage to the Antarctic Peninsula and South Georgia, working as Deputy Expedition Leader aboard MV Greg Mortimer, our ship experienced an outbreak of Covid-19, .

Through the voyage our expedition team remained upbeat and resilient, with one or two quiet moments when the exit home, which seemed possible one day, became unattainable the next. During that rollercoaster it felt important that the concept of home—of getting home—remained in focus. Onboard we got to talking about what each of us would do when the happy day came. For kayaking guide Dan it was reuniting with the Australian bush, the smell of the air, standing at a lookout. For climatologist Ian, it was deciding which from his collection of surfboards would best fit the happy task of hitting the surf at Sydney’s northern beaches. For expedition leader Flo returning to the Netherlands, it was visiting her parents and sitting down to her Mum’s legendary cooking. For all in the team, after reuniting with loved ones, came a wish to reconnect with nature and the outdoors, to return to the simple domesticities of home cooking, baking, and easy conversations far removed from Covid-19.

- Our Expedition Team: Back L–R: Mountaineer Kevin, Doctor Jeff, Historian Carol, Climatologist Ian, Mountaineer Jane, Naturalist Alan, Photographer Peter. Front L–R: Naturalist Isabelle, Assistant Expedition Leader Thérèse, Expedition Leader Florence, Deputy Expedition Leader Robyn. Absent: Naturalist Roger, Kayaking guides Daniel, Matthias, Eamon, Expedition Coordinator Justine, Zodiac Master Sergeii, Mudroom & Shopkeeper Reza.

The image that stood as my beacon was one of working in our garden. I am no gardening guru, but along with my partner Gary we are tragics, mostly to find out what we should already have done in our garden where it’s survival of the fittest, and where we gain joy from the vegetables we manage to grow. The vision I held was planting the organic garlic I’d ordered before leaving home.

During hotel quarantine I looked to another goal. Trials had begun using Covid Convalescent Plasma; that is, extracting antibody-rich plasma from post-Covid donors to use for experimental transfusion and research into finding a vaccine. Along with some of my expedition team mates, I contracted Covid-19 aboard. Just to have got through it, to be well, has me so grateful to be alive. I wanted one small good thing to come from all the bad. Donating my plasma seemed to fit the bill.

I am partway through writing my third novel, a story set in the High Arctic with a reference to the 1918 Spanish Influenza. Well before Covid-19 I had done due research on the virus, studied statistics, read articles detailing the influenza’s devastating symptoms that targeted young, strong adults, often men, and those who cared for them. This verse of the time, skipped to by children on the streets, found a place in my story: I had a little bird / Its name was Enza / I opened the window / And in-flu-enza

I thought I understood something about the fear of contracting such a virus but until Covid-19, I never gave enough thought to how fear might transfer to stigma, a mark of disgrace that gives rise to shame, not just for those struck down but for loved ones in the same vulnerable household. In my novel-in-the-making I imagine the grief of a bereaved young widow speared with lonely solitude, friends, family members, even the local priest keeping a safe distance from the ‘Unclean’.

Five weeks after testing positive for Covid, I battled the State’s Health Department to be retested. Their resistance held logic in that PCR nasal testing post-Covid may return a positive result if a swab picks up dead, inactive virus. I was repeatedly told the test was ‘not recommended’, that any positive result would be discarded as misleading. Fourteen asymptomatic days in isolation was considered sufficient quarantine. I was close to finishing 28 days. Put it down to obsession, dogged determination, or simply an emotional vulnerability that comes with having had the virus: that rationale, those assurances, refused to settle. Even if the risk of contagion was deemed non-existent, or minuscule, I shuddered at the consequences of passing on the virus to my partner at home, to friends and those in the community who may be vulnerable. During one phone call I asked the health practitioner, ‘Is ‘not recommended’ a euphemism for refusal?’ ‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘I don’t make the rules.’

When it looked as if retesting would be denied me, I announced to a group of local friends, people I was likely to have some contact with, that I had contracted Covid-19. Any misinterpretation is my own, but what I felt in response was anxiety, even alarm. The subject soon turned to lighter-hearted topics. I felt dispirited. If good friends, all smart and kind, felt apprehensive, how would it be telling someone who was not so smart, not so kind? My courageous friend Jenny proclaimed that she would be coming around to visit me as soon I got out of quarantine, keeping social distancing exactly as she had been with everybody else. I had other strong support. I valued conversations with my good friend Dr Ann, a ship’s doctor currently working on a Covid ward in South West WA. Ann is fascinated by the epidemiology of the virus and remains actively busy keeping up with latest findings. Hers was an evidence-based voice of reason, talking through things that aren’t yet known, that are changing by the week, along with what seems to be consistent findings. Our tour company, too, had thoughtfully contracted Kristen, a New Zealand counsellor, available to those of us on the ship. She is a no-nonsense, evidence-based psychologist who has spent years working with front line responders such as firefighters, medics and soldiers. In my final, fourth week of quarantine I have her to thank for prising me from the solitary confinement of my hotel room, down to the hotel’s ballroom modified to a walking circuit where there is a strict limit on numbers to ensure adequate social distancing. I would venture down at meal times to clock up some laps.

The Grand Ballroom transformed in a quarantine walking circuit

A few days before I was due to go home, my ongoing requests for Covid testing finally reached the State’s Director of Public Health. The Department relented. I took a deep breath. A positive result would likely do my head in—could I trust it to be a false positive, might I still be contagious? I had to know, come what may. Ambulance transport arrived at the hotel and whisked me away to a pathology centre for a PCR nasal test. Twenty-four hours later the result returned ‘No Covid-19 detected’.

On arriving home and doubling my garlic order, Gary asked if I was branching into garlic farming. I’d been inspired by Letitia at who taught me more about garlic during a single phone chat than I’d ever known. Five varieties to suit different cooking styles, staggered times of harvesting, a range of storage capacities—a far cry from the unidentified garlic we bunged in last winter, this season’s elaborate array well beyond our personal needs and my dodgy cooking prowess. I didn’t care. Turning over the soil and planting those eighty cloves proved every bit as heavenly as the shipboard anticipation.

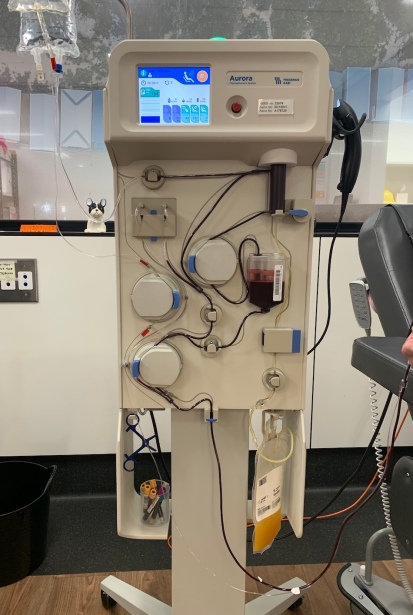

Now, seven weeks post-Covid, I understand and empathise with the fear I see and feel around the virus. There’s nothing quite the “social distancer” as telling people you’ve had Covid. I have had people literally take an extra step back as I rush to assure them that I am now Covid-free. Stigma, the shame it carries, are big human emotions to wrestle, but rocking up to this week to donate my second round of plasma continues to be a celebratory experience. The Centre is a happy place of wellness, its practitioners capable and genuinely enthusiastic professionals who are doing good work to help us all.

Donating Covid plasma at Hobart’s Red Cross Life Blood Centre

Covid postscript: a Covid study of all who were aboard MV Greg Mortimer is the subject of a scientific paper recently published in the , the results significant for the cruising industry.

Gardening postscript: local garlic lovers, all being well, next summer I hope to have a bounty of produce and will be delighted to share.

Photos ©Robyn Mundy 2020

Wonderful articles on your experience with Covid-19, the quarantine on board a ship, and the readjustment to life back home. You have really given some great insights into what many have been going through in the time of Covid-19. So glad you’re well now and donating your plasma – good on you!

Wendy x

LikeLike

Thank you, Wendy. I really appreciate your interest. Keep safe and happy. WA is doing so well.

LikeLike

Beautiful words. You are a courageous woman, Robyn. I can only imagine the fear and stigma you experienced but liken it to arriving in Australia in the post-white Australia days when people assumed that my not-quite-white skin would somehow rub off and contaminate them. I’m so happy to hear that you are gardening. It’s such a grounding, peaceful activity. I too, am growing garlic for the first time. I wish you many plump heads to harvest in the summer! And I look forward to reading your book. Be well. xx

LikeLike

Thank you, Colleen. A dehumanising experience of arriving in Australia. It must have felt bewildering. Where would we now be as a nation without our rich cultural diversity.

Yours in happy garlic growing. Robyn x

LikeLike

Great writing Robyn! And what a great experience for helping you to understand the pervading emotions in the time of the Spanish flu!! Amazing to think you have had this experience and can write and make sense of it⦠Love Ann xxx

>

LikeLike

Thanks, Ann. And a huge heartfelt thanks for our interesting chats and your friendship through this crazy time. 🙏

LikeLike

Bravo, Robyn! May those feelings of stigma fade from your life but provide even more depth to the novel you’re writing. Not a recommended research method, but still… 🙂 xx

LikeLike

😁 I am with you on all of that. Thanks, Amanda.

LikeLike