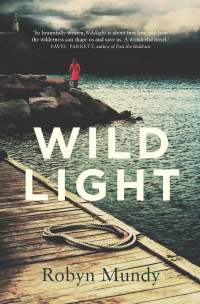

Any title that includes Rainbow is bound to conjure images of crystals and incense sticks. Nope, there’s not a tinkle of glass nor a whiff of sandalwood to be found in this post, only photographic proof that it is possible to see the end of the rainbow, and live a serene life beneath it. We’re talking Maatsuyker Island, site of Australia’s southernmost lighthouse, the island where my novel Wildlight plays out, within cooee of the south-west corner of Tasmania.

Our six months of caretaking and weather observing at Maatsuyker Island has come to a close. Now, even more than our first few days of treading paved roads, it feels like crashing back to earth. The work on the island was hard, the living conditions cold, and the wind rarely stopped blowing, but perhaps all these challenges contributed to us having the time of our lives. And even though we turned into eating machines, we each left the island many kilograms lighter, and fitter, thanks to hauling lawnmowers up and down slopes, wielding brush cutters, digging drains and tending a large vegetable garden, plus all the walking. It’s a win-win formula that I’m naming The Maatsuyker Diet.

Here is my partner Gary with ‘Helga’ the mower. There’s little scope for traditional gender roles on Maatsuyker Island. We divided the mowing and brush cutting work that tends a 2-kilometre-long grass road, 2 helicopter pads, 1 vegetable garden, the surrounds of 3 cottages and 1 lighthouse, 1 paddock, and brush cutting 7 bush tracks, paths and numerous slopes too tricky or hazardous to mow. One round took each of us 4–5 days on a 3-weekly cycle.

A corner of the Maatsuyker pantry at the start of our stay; strawberries from the veggie garden’s poly house; sushi rolls for dinner (my partner Gary’s speciality); during our stay we consumed 42 kgs flour transformed into sourdough loaves and baked goods.

During our first caretaking term in 2010–11 we barely saw another two-legged being, but on this stint we relished the company of several energetic visitors. Long-time friends Katherine and Kevin from Western Australia arrived on a crayfishing boat and stayed for five days. The permits and arrangements took them months, and even then it was nail biting times as the ocean swell and weather was against them both on their arrival and throughout their stay. Katherine and Kev were thankful for the handrails in the howling gales; they very quickly found their footing, embraced nature, and contributed to Maatsuyker with all manner of island work.

The wonderful Friends of Maatsuyker stayed over for two intensive working bees. This volunteer group contributes to almost every aspect of the island. Amongst the hard workers was Mark, who has turned his passion for lighthouses into restoring those around Australia that require serious TLC. Mark made his own way down to Tasmania and donated time and skills to continue work on restoring Maatsuyker’s lighthouse. During his days on the island we would regularly cross paths at first light as he headed down the hill to begin his day, working until late into the nights. He made impressive progress by removing damaging paint from a big section of the inside walls, and repainting top parts of the tower.

An unexpected visitation came from Dutch presenter-producer Floortje Dessing and her camerawoman Renée, who flew all the way from the Netherlands at short notice to produce a documentary about life as caretakers on Maatsuyker Island. () is a popular Dutch TV series which focusses as much on the people who choose to live in remote corners of the world as it does on the the natural wonders of wild places. While they were on Maatsuyker the girls got to experience the brunt of the Roaring Forties latitudes with 6-metre ocean swells and a record wind gust for January. Maatsuyker claims plenty of ‘personal bests’ when it comes to record winds: still to be beaten is its August 1991 squall of 112 knots (207.4 kms per hour), the country’s highest non-cyclonic wind gust. Floortje and Renée embraced every moment of the weather and were fun to be with. I only learned later how big a celebrity Floortje is in her home country, while to us they were simply two sparkling, energetic women who joined us each evening for dinner, washed up afterwards, brought a whopping great round of Edam cheese in their suitcase and followed us here and there on our daily routines.

Lastly we welcomed Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife video competition winner Simon whose prize was a visit to Maatsuyker Island. Simon and his mate Noodle lobbed in for an overnight stay via helicopter, though with under-par weather conditions it was touch and go whether they could even make it to the island. Thanks to the skilled pilots at they arrived safely after a short delay. Without losing another minute, the boys donned wet weather gear and bounded from one end of the island to the other with cameras in tow. In the evening, between ducking outdoors to watch a brilliant sunset, they joined us at Quarters 1 for curry and a pint of home brew beer. Next morning at 0400 they were up and at ’em to watch Maatsuyker’s thousands of short-tailed shearwaters launch off the island. In 24 hours Simon and Noodle succeeded in filming and later producing a professional 3-minute video which showcases the island. I will have that clip available to share in a week or so, along with an interview with Simon.

I could go on about Maatsuyker, but will close with the info below and a selection of photos which I hope express the magic of the island.

The nitty gritty of caretaking at Maatsuyker Island

The volunteer caretaker program is coordinated and managed by who currently advertise the position through . every two years. Each applicant must demonstrate a range of skills and an adequate level of physical fitness, and will be responsible for purchasing their own provisions for the six-month term. Part of the Maatsuyker caretaker duties is to conduct daily weather observations for the . Many short-term volunteer caretaking opportunities across Tasmania are advertised through ., the incorporated community partner organisation that provides management and support for volunteers working in natural and cultural heritage conservation and reserve management. (Wildcare Inc.) is a volunteer group who contribute time and skills to the island, raise funds towards maintenance and improvements on Maatsuyker, run day trips to the island via boat, and conduct annual working bees.

With my times away from home, my blogging pattern tends to be feast or famine. This week sees no nutritional lack. Despite spotty attendance I feel great personal reward in the interactions with readers and guests that maintaining a website generates. Imagine, then, a world with no internet, no email and no mobile coverage; then—as daunting as the prospect may be—picture me in that world for the next six months. Shortly, my partner Gary and I are off to remote

With my times away from home, my blogging pattern tends to be feast or famine. This week sees no nutritional lack. Despite spotty attendance I feel great personal reward in the interactions with readers and guests that maintaining a website generates. Imagine, then, a world with no internet, no email and no mobile coverage; then—as daunting as the prospect may be—picture me in that world for the next six months. Shortly, my partner Gary and I are off to remote

My first novel,

My first novel,  As a contemporary Antarctic novelist, I am not alone in this draw to the frozen south. Favel Parret’s has its origin in the history of Nella Dan, a former Australian Antarctic supply vessel. I posed the question to Favel: what attracts you to wild places?

As a contemporary Antarctic novelist, I am not alone in this draw to the frozen south. Favel Parret’s has its origin in the history of Nella Dan, a former Australian Antarctic supply vessel. I posed the question to Favel: what attracts you to wild places? Author Jesse Blackadder also travelled south to understand Antarctica. Her novel draws on the 1930s history of Ingrid Christensen, wife of a Norwegian whaling magnate. Ingrid and two unlikely female companions are each poised to become the first woman to land on Antarctica. Serendipitously, I recently met up with Jesse and asked which came first, the draw to Antarctica, or Ingrid’s story? Like me, like Ingrid Christensen, Jesse’s personal longing to experience Antarctica stretched back years, driven, in Jesse’s case, by images of wildlife and ice. Place first, story second.

Author Jesse Blackadder also travelled south to understand Antarctica. Her novel draws on the 1930s history of Ingrid Christensen, wife of a Norwegian whaling magnate. Ingrid and two unlikely female companions are each poised to become the first woman to land on Antarctica. Serendipitously, I recently met up with Jesse and asked which came first, the draw to Antarctica, or Ingrid’s story? Like me, like Ingrid Christensen, Jesse’s personal longing to experience Antarctica stretched back years, driven, in Jesse’s case, by images of wildlife and ice. Place first, story second. My new novel

My new novel

way on a yacht; naturally I was wondering what the heck I was doing and what awaited me on the high seas. Somewhat unexpectedly, the palm reader told me I would live surrounded by cows. Naturally I dismissed him as a phony but in fact he turned out to be right. Ever since I have been surrounded by cows — up in the Whitsundays for ten years and now down here in Bega on the far south coast of New South Wales. When I look up from my

way on a yacht; naturally I was wondering what the heck I was doing and what awaited me on the high seas. Somewhat unexpectedly, the palm reader told me I would live surrounded by cows. Naturally I dismissed him as a phony but in fact he turned out to be right. Ever since I have been surrounded by cows — up in the Whitsundays for ten years and now down here in Bega on the far south coast of New South Wales. When I look up from my JS: Oddly enough, when I was about twenty I woke up one morning with the thought in my head that I was going to be an editor, even though I didn’t have the first clue what an editor did. I was at uni in England at the time and the careers adviser laughed at me and told me I should become an accountant. Thankfully I came to Australia instead because I have the sneaky suspicion I would have ended up in jail for embezzlement. In Sydney I sent out my cv to every publisher in town, still completely ignorant of what an editor did. Thankfully James Fraser, then the publishing director at Pan Macmillan, offered me a job as his secretary. Whilst I was proving myself incompetent at that I was given the opportunity to read through the slush pile and then eventually to learn from two very skilled editors – Jane Palfreyman and Fiona Giles – who gradually trained me up into an editing role.

JS: Oddly enough, when I was about twenty I woke up one morning with the thought in my head that I was going to be an editor, even though I didn’t have the first clue what an editor did. I was at uni in England at the time and the careers adviser laughed at me and told me I should become an accountant. Thankfully I came to Australia instead because I have the sneaky suspicion I would have ended up in jail for embezzlement. In Sydney I sent out my cv to every publisher in town, still completely ignorant of what an editor did. Thankfully James Fraser, then the publishing director at Pan Macmillan, offered me a job as his secretary. Whilst I was proving myself incompetent at that I was given the opportunity to read through the slush pile and then eventually to learn from two very skilled editors – Jane Palfreyman and Fiona Giles – who gradually trained me up into an editing role. JS: I love your description of the editing of Wildlight and that was exactly what I hoped for. More than anything I want a writer to learn to trust themselves – as you say, to feel empowered to trust in their own creative capacity. It’s very satisfying when an author says, yes, I knew that wasn’t quite right but I didn’t know how to fix it, and then, simply through the process of having their manuscript reflected back to them, they find exactly the right solution. This is a very enlivening process, for them and for me.

JS: I love your description of the editing of Wildlight and that was exactly what I hoped for. More than anything I want a writer to learn to trust themselves – as you say, to feel empowered to trust in their own creative capacity. It’s very satisfying when an author says, yes, I knew that wasn’t quite right but I didn’t know how to fix it, and then, simply through the process of having their manuscript reflected back to them, they find exactly the right solution. This is a very enlivening process, for them and for me.

— Once media coverage starts to be confirmed, the author is provided with an outline of the media due to take place for the book, and receives regular updates on media coverage and any interview requests.

— Once media coverage starts to be confirmed, the author is provided with an outline of the media due to take place for the book, and receives regular updates on media coverage and any interview requests.